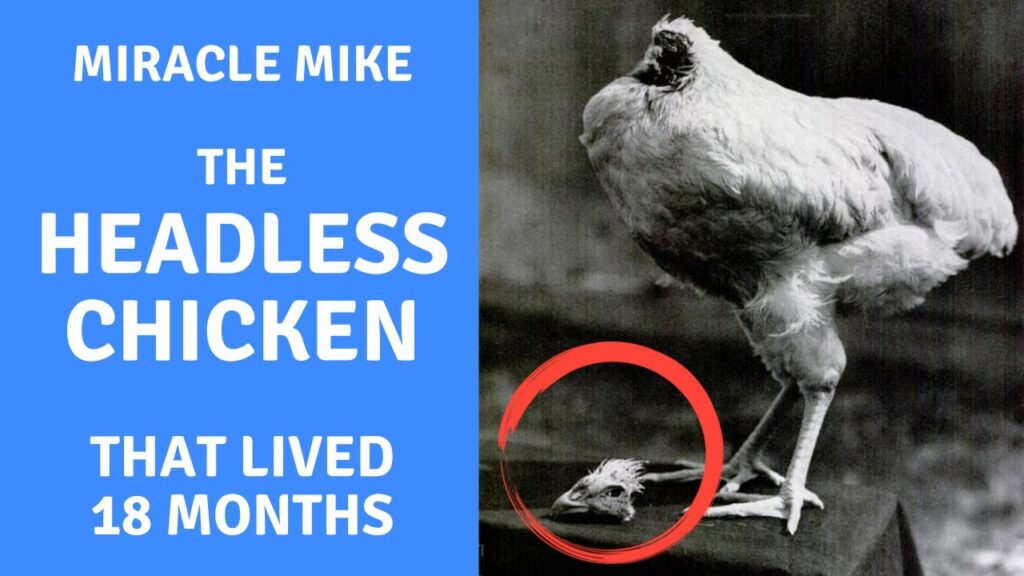

Seventy years ago, a farmer beheaded a chicken in Colorado, and it refused to die. Mike, as the bird became known, survived for 18 months and became famous. But how did he live without a head for so long, asks Chris Stokel-Walker.

SOURCE: BBC.

On 10 September 1945 Lloyd Olsen and his wife Clara were killing chickens, on their farm in Fruita, Colorado. Olsen would decapitate the birds, his wife would clean them up. But one of the 40 or 50 animals that went under Olsen’s hatchet that day didn’t behave like the rest.

“They got down to the end and had one who was still alive, up and walking around,” says the couple’s great-grandson, Troy Waters, himself a farmer in Fruita. The chicken kicked and ran, and didn’t stop.

It was placed in an old apple box on the farm’s screened porch for the night, and when Lloyd Olsen woke the following morning, he stepped outside to see what had happened. “The damn thing was still alive,” says Waters.

“It’s part of our weird family history,” says Christa Waters, his wife.

Waters heard the story as a boy, when his bedridden great-grandfather came to live in his parents’ house. The two had adjacent bedrooms, and the old man, often sleepless, would talk for hours.

“He took the chicken carcasses to town to sell them at the meat market,” Waters says.

“He took this rooster with him – and back then he was still using the horse and wagon quite a bit. He threw it in the wagon, took the chicken in with him and started betting people beer or something that he had a live headless chicken.”

Word spread around Fruita about the miraculous headless bird. The local paper dispatched a reporter to interview Olsen, and two weeks later a sideshow promoter called Hope Wade travelled nearly 300 miles from Salt Lake City, Utah. He had a simple proposition: take the chicken on to the sideshow circuit – they could make some money.

“Back then in the 1940s, they had a small farm and were struggling,” Waters says. “Lloyd said, ‘What the hell – we might as well.'”

First they visited Salt Lake City and the University of Utah, where the chicken was put through a battery of tests. Rumour has it that university scientists surgically removed the heads of many other chickens to see whether any would live.

It was here that Life Magazine came to marvel over the story of Miracle Mike the Headless Chicken – as he had by now been branded by Hope Wade. Then Lloyd, Clara and Mike set off on a tour of the US.

They went to California and Arizona, and Hope Wade took Mike on a tour of the south-eastern United States when the Olsens had to return to their farm to collect the harvest.

The bird’s travels were carefully documented by Clara in a scrapbook that is preserved in the Waters’s gun safe today.

People around the country wrote letters – 40 or 50 in all – and not all positive. One compared the Olsens to Nazis, another from Alaska asked them to swap Mike’s drumstick in exchange for a wooden leg. Some were addressed only to “The owners of the headless chicken in Colorado”, yet still found their way to the family farm.

After the initial tour, the Olsens took Mike the Headless Chicken to Phoenix, Arizona, where disaster struck in the spring of 1947.

“That’s where it died – in Phoenix,” Waters says.

What happens when a chicken’s head is chopped off?

- Beheading disconnects the brain from the rest of the body, but for a short period the spinal cord circuits still have residual oxygen.

- Without input from the brain these circuits start spontaneously. “The neurons become active, the legs start moving,” says Dr Tom Smulders of Newcastle University.

- Usually the chicken is lying down when this happens, but in rare cases, neurons will fire a motor programme of running.

- “The chicken will indeed run for a little while,” says Smulders. “But not for 18 months, more like 15 minutes or so.”

Mike was fed with liquid food and water that the Olsens dropped directly into his oesophagus. Another vital bodily function they helped with was clearing mucus from his throat. They fed him with a dropper, and cleared his throat with a syringe.

The night Mike died, they were woken in their motel room by the sound of the bird choking. When they looked for the syringe they realised they had left it at the sideshow, and before they could find an alternative, Mike suffocated.

“For years he would claim he had sold [the chicken] to a guy in the sideshow circuit,” Waters says, before pausing. “It wasn’t until, well, a few years before he died that he finally admitted to me one night that it died on him. I think he didn’t ever want to admit he screwed up and let the proverbial goose that lays golden eggs die on him.”

Olsen would never tell what he did with the dead bird. “I’m willing to bet he got flipped out in the desert somewhere between here and Phoenix, on the side of the road, probably eaten by coyotes,” Waters says.

But by any measure Mike, bred as a fryer chicken, had a good innings. How had he been able to survive for so long?

The thing that surprises Dr Tom Smulders, a chicken expert at the Centre for Behaviour and Evolution at Newcastle University, is that he did not bleed to death. The fact that he was able to continue functioning without a head he finds easier to explain.

For a human to lose his or her head would involve an almost total loss of the brain. For a chicken, it’s rather different.

“You’d be amazed how little brain there is in the front of the head of a chicken,” says Smulders.

It is mostly concentrated at the back of the skull, behind the eyes, he explains.

Reports indicate that Mike’s beak, face, eyes and an ear were removed with the hatchet blow. But Smulders estimates that up to 80% of his brain by mass – and almost everything that controls the chicken’s body, including heart rate, breathing, hunger and digestion – remained untouched.

It was suggested at the time that Mike survived the blow because part or all of the brain stem remained attached to his body. Since then science has evolved, and what was then called the brain stem has been found to be part of the brain proper.

“Most of the bird brain as we know it now would actually be considered the brain stem back then,” Smulders says.

“The names that had been given to parts of the bird brain in the late 1800s were all indicating equivalences with the mammalian brain that were in fact wrong.”

Why those who tried to create a Mike of their own did not succeed is hard to explain. It seems the cut, in Mike’s case, came in just the right place, and a timely blood clot luckily prevented him bleeding to death.

Troy Waters suspects that his great-grandfather tried to replicate his success with the hatchet a few times.

Certainly, others did. A neighbour who lived up the road would buy up any chickens for sale at an auction in nearby Grand Junction, Colorado, and stop by the family farm with a six-pack of beer for Olsen, to persuade him to explain exactly how he did it.

“I remember [him] telling me, laughing, that he got free beer every other weekend because the neighbour was sure he got filthy rich off this chicken,” Waters says.

“Filthy rich” was an opinion many held in Fruita of the Olsen family. But according to Waters, that was an exaggeration.

“He did make a little money off it,” Waters says. He bought a hay baler and two tractors, replacing his horse and mule. And also – a bit of a luxury – a 1946 Chevrolet pickup truck.

Waters once asked Lloyd Olsen if he had fun. “He said, ‘Oh yeah, I had a chance to travel around and see parts of the country I probably otherwise wouldn’t have seen. I was able to modernise and have farm equipment.’ But it was something he put in his past.

“He still farmed the rest of his life, scratched a living out of the dirt.”